What is cocaine and what are the effects of cocaine on the body?

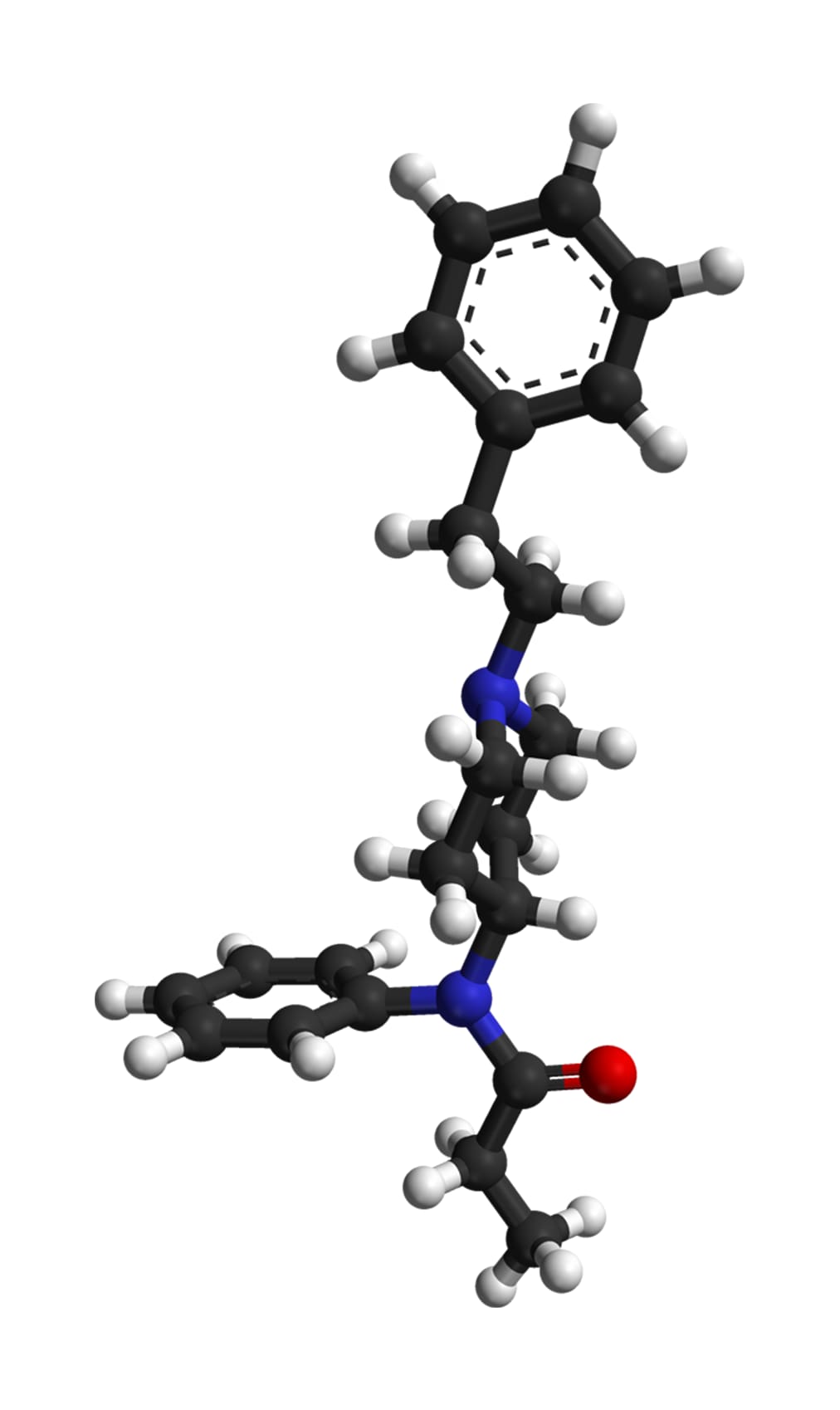

Cocaine is a human-made stimulant drug extracted from the leaves of the coca plant.

Cocaine is a human-made stimulant drug extracted from the leaves of the coca plant. It is grown in the Andean region of South America. Cocaine can boost mood, energize, reduce appetite, and make someone more awake and alert. Cocaine also raises blood pressure, increases body temperature, and increases heart rate. In high doses, it can also make someone feel anxious or paranoid. Overdosing on cocaine can cause seizures, stroke, or heart attack. Starting at a low dosage and going slow when using cocaine can help avoid overdose.

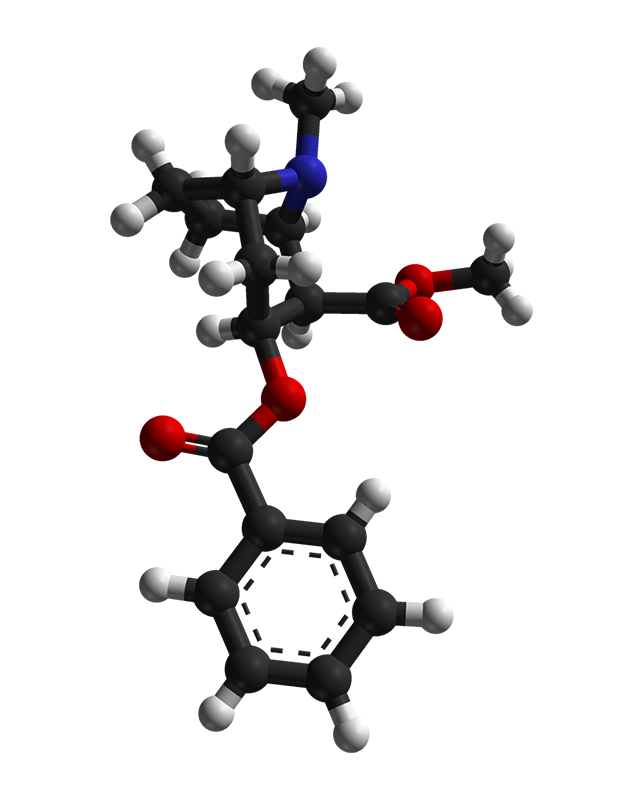

In 2021, an estimated 4.8 million people used cocaine in the US in the past year, including 996,000 people who used crack cocaine. Crack cocaine is made by processing powder cocaine with ammonia or baking soda.

Powder cocaine and crack cocaine are similar, but the penalties differ

There are no pharmacological differences between powder cocaine and crack cocaine. This means that they are nearly identical and produce similar effects in the body. The way that the drugs are used can affect how quickly their effects are felt. Powder cocaine is usually snorted, which can delay the effects but can make them last longer. Crack cocaine is typically smoked, so its effects are felt faster, and the high lasts a shorter time.

Although these drugs are nearly identical, the punishment for crack possession or sales is far greater than for powder cocaine. Until 2010, there was a 100 to 1 sentencing disparity between powder cocaine and crack cocaine. This meant that 5 grams of crack carried a 5-year mandatory minimum sentence, but it took 500 grams of powder cocaine to trigger the same sentence. The sentencing disparity has had a disproportionate impact on poor people and people of color. Statistics show that Black people are more likely to be convicted of crack cocaine offenses compared to white people, even though the majority of people who use crack cocaine are white. Meanwhile, white people are more likely to be convicted of powder cocaine offenses.

The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 reduced the sentencing disparity to 18 to 1. Research found that this “reduced the disparity between crack and powder cocaine sentences, reduced the federal prison population, and… resulted in fewer federal prosecutions for crack cocaine… while crack cocaine use continued to decline.” In 2022, the Department of Justice directed prosecutors to charge crack offenses as powder cocaine offenses, and to seek sentences for crack that are consistent with those for powder cocaine. While the Fair Sentencing Act and the DOJ’s guidance are positive steps forward, federal legislation is needed to end the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine once and for all.

Cocaine use, pregnancy, and outcomes

In the 1980s, politicians and the media warned that crack cocaine use during pregnancy was creating a generation of so-called “crack babies” with lifelong health problems. This was a moral panic with racist undertones, and not based in science. Some research suggests that cocaine exposure can slow fetal growth. But it is hard to separate cocaine-related health effects from other factors like poverty and lack of prenatal care. It is not clear that cocaine exposure alone leads to lasting developmental or behavioral problems in childhood. This is because social and environmental factors can play a significant role in how a child develops. Children from nurturing and stimulating environments perform better, regardless of cocaine exposure.