After many years, overdose deaths are finally going down because of public health solutions. The CDC shows overdose deaths in the United States fell 17% between July 2023 and July 2024.

Health and harm reduction tools, like the opioid-reversal drug naloxone and fentanyl test strips, have kept tens of thousands of people alive. More people are benefitting from policies to expand access to treatments like methadone and buprenorphine. These are medications that reduce opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms, while cutting overdose risk in half. This is in addition to the reality that fewer people are using street opioids in some parts of the country, so fewer people are at risk of accidentally consuming fentanyl.

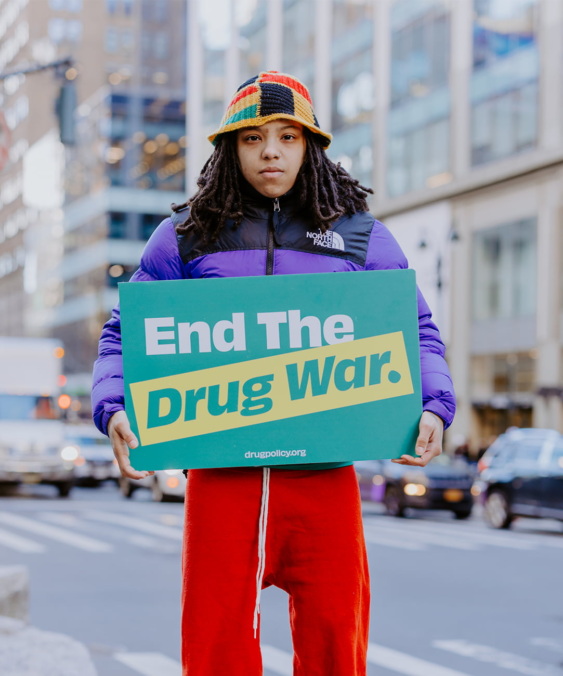

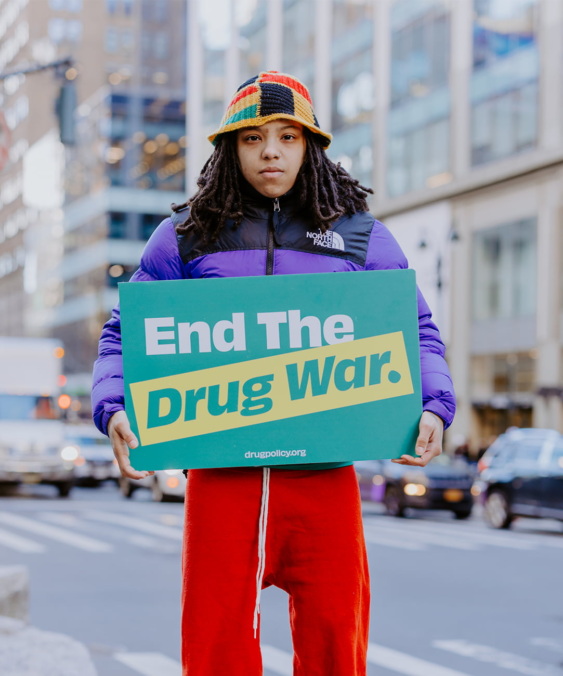

But it’s likely there will still be nearly 100,000 overdose deaths in 2024. It’s urgent that our elected leaders follow what works, rather than expanding disproven efforts like drug enforcement and locking people up for addiction. To save lives, it’s critical that elected leaders go all in on a public health approach to drugs—providing better access to health and harm reduction services, treatment, and drug education based in facts, not fear.

Dr. Sheila Vakharia, DPA’s deputy director of Research and Academic Engagement, has been researching the drops in overdose deaths. We sat down with her to learn more, including what we and our elected leaders can do to save lives.

It’s several factors that may be at play, and all point to why public health approaches to drugs and overdose are critical and lifesaving.

First, it’s important to remember that fentanyl entered our drug supply only after crackdowns on prescription opioids led drug dependent people to seek a new source of opioids. Then the illegal market responded to this enormous demand by cutting heroin with fentanyl to make it stronger. Now, pure fentanyl is the norm, and even stronger drugs are emerging, like xylazine and nitazenes. Evidence and history show that crackdowns only lead to more dangerous drugs. In fact, the federal government criminalized all fentanyl-related substances in 2018, and overdose deaths rose 60%—from 67,367 in 2018 to 107,941 deaths in 2022.

If you look at data from Customs and Border Protection, you’ll see that fentanyl seizures nearly doubled between fiscal year 2021 and 2023. Yet during that time, overdose deaths remained high. Even the DEA claimed that fentanyl was still available on our streets. Then, in fiscal year 2024, fentanyl seizures decreased nearly 19%—and data suggests overdose deaths declined. Drug seizures often fluctuate on an annual basis, and it is hard to draw a connection between seizures and deaths.

| Fiscal Year (Oct-Sep) |

Total Weight of Fentanyl Seizures (lbs.) |

|---|---|

| 2021 | 11.2k |

| 2022 | 14.7k |

| 2023 | 27.0k |

| 2024 | 21.9k |

Drug expert Dr. Joseph Palamar from New York University has been quoted as saying we do not have enough information on the drug supply to know how much fentanyl made it into the country. Any claims that try to connect increase in seizures to decrease in overdose deaths are overblown and unfounded.

It’s unclear whether the potency of pills has changed. The only way to potentially answer this question is from the DEA’s testing of a small portion of pills they seize annually. They have used the arbitrary cutoff of 2 mg of fentanyl per pill to indicate a “lethal” amount of fentanyl in samples. DEA Administrator Anne Milgram recently claimed that in 2024, fewer seized pills had a lethal amount of fentanyl in them due to U.S. efforts abroad (yet the public has not been given access to 2023 or 2024 reports).

However, not all counterfeit pills come over the border in that form. Sometimes powders come over the border, and they are then mixed with other adulterants and pressed into counterfeit pills domestically in the U.S. It is impossible to judge the potency of all counterfeit pills circulating in our underground drug supply based on a small sample. It is also difficult to trace the potency of counterfeit pills to U.S. policies targeting cartels in Mexico.

In addition, fentanyl powder remains the dominant form of fentanyl used on the East Coast, where the majority of overdoses occur. Reduced potency in pills may not have as large of an impact as changing potency in powder.

Polysubstance use, or using more than one drug at a time, is also a driver for overdose. So we must also remain aware of the role that other drugs continue to play in overdose deaths, such as methamphetamine, cocaine, xylazine, medetomidine, nitazenes, and others.

In 2019, China scheduled, or criminalized, fentanyl. But U.S. fentanyl overdoses reached record highs in 2020 because China became a supplier of precursors. (Precursors are the chemical building blocks to make certain synthetic drugs.) The Biden Administration finally sat down with Chinese officials in fall 2023, after two years of China not engaging in much domestic drug law enforcement to target people who were selling these precursors abroad.

After these talks, China scheduled some fentanyl precursors, the nitazene class of drugs, and they promised to regulate xylazine. But these changes only went into effect on September 1, 2024. We cannot attribute reduced overdose deaths to any of these changes, since they are very recent.

Yes. While many states saw reductions, some states saw increases in overdose deaths. This is particularly true in the northwest and west—places where fentanyl only arrived recently. And some cities and states saw small reductions, or deaths remained relatively stable—for instance, overdose deaths in NYC only dropped by 1% in 2023.

In some cities, states, and regions, overdose deaths remained high or increased among certain marginalized groups. These include racial and ethnic minorities, unhoused or unstably housed people, people involved with the criminal legal system, and others. These individuals tend to be some of the most vulnerable to overdose deaths. This is why we must make meaningful investments in housing, affordable and evidence-based treatment, as well as harm reduction and overdose prevention services.

While we are still trying to understand the reasons why overdose deaths went down, it’s becoming clearer that public health interventions have played a pivotal role. It is not time to slow down our efforts. People are still dying—more than 93,000 between June 2023 and 2024. This number is still higher than pre-COVID. Our elected leaders must prioritize and go all in on a public health response that keeps our communities safe and provides better access to health, harm reduction, and treatment services.

Read our fact sheet Health, Harm Reduction Approaches Pivotal to Decrease in National Drug Overdose Deaths to learn more about why overdose deaths are decreasing.